The Art of Mochi Making

A few shrines in Tokyo still celebrate the traditional production of mochi – rice cake- with a small festival around New Year.

For more than 2,000 years, rice has been a major agricultural fixture in Japan and a symbol of the nation’s spiritual connection with nature, the gods and the community.Rice (and rice wine) is therefore among the offerings at the Shinto shrines a nearly every ceremony. An annual custom is mochitsuki—the pounding of mochi or rice cakes, which is essential to New Year’s celebration. Mochitsuki, done in the family, is an all-day event which requires many hands, long hours, and physical labor, but is also a time of fellowship and socializing with friends and family.

In Tokyo there are still a few shrines which celebrate a mochitsuki in January. One is the Daita-Hachiman-Shrine in Setagaya -ku. The actual making of rice cakes was embedded into the traditional shinto ceremony. Let´s go step by step.

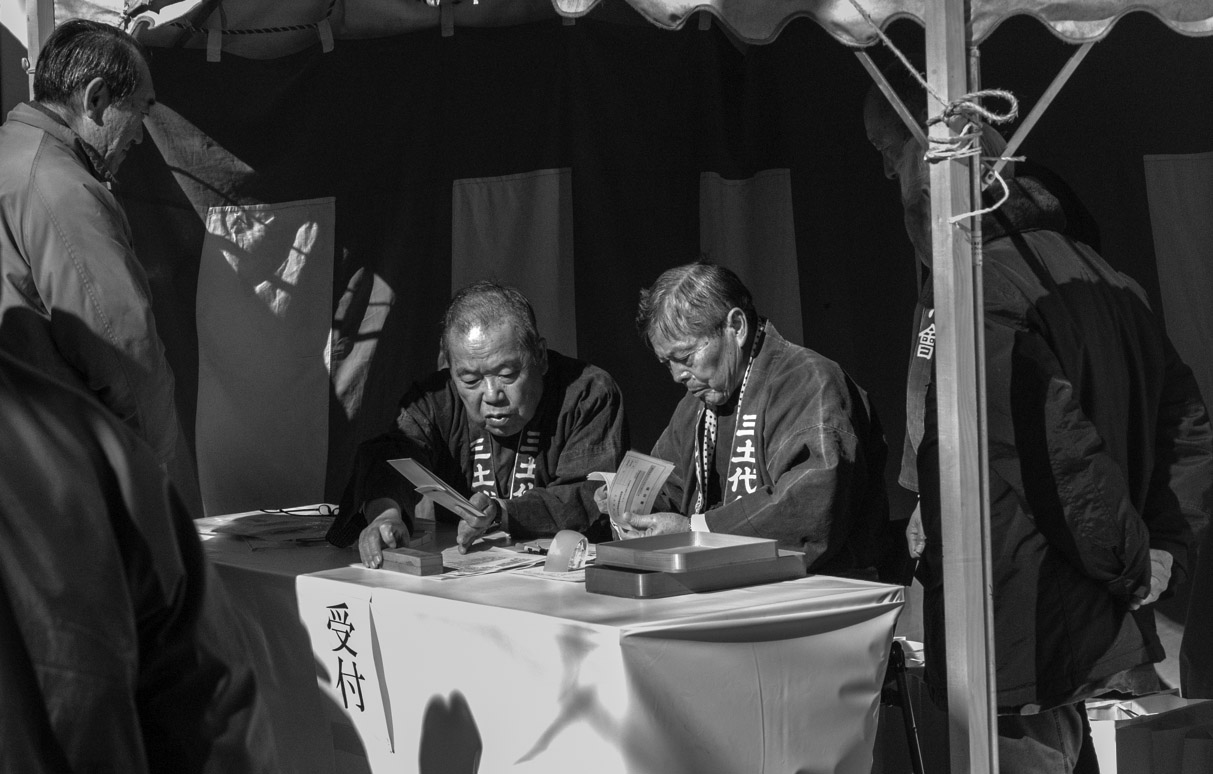

Preparations at the shrine where going on when I arrived. The priest checked the setting and people still were signing up to be seated as special guests in a small tent on the left side.

Then the priests entered followed by the local group of men who would perform the mochitsuki and some women who would give away the mochi to the public, among them a class from elementary school.

Next the pries purified the small altar set up for the ceremony and men and women with a tamagushi- a branch of the sakaki-tree. The main priest continued with a prayer.

Later the special guests- among them some members of the Japanese Parliament, local officials, the head of the local bank etc…– were given a tamagushi to present to the kami (gods).

The whole ceremony continued for one hour. But then the team got ready for work by moving the altar away and taking of the lid from the usu, or mortar, made from a wood stump.Next to it is a basket of fresh water.

Mochitsuki actually begins the day before, with the washing of the mochigome (sweet glutinous rice) and leaving it to soak overnight in large kettles or tubs. Early the next morning the mochigome is ready to be steamed in the seiro—wooden steaming frames. Three or four seiro are stacked one on top of the other and placed over a kettle of boiling water.The work starts with the first seiro arriving and being put into the usu.

The hot cooked rice in the usu is in principle pounded with a kine or wooden mallet.At the beginning the rice is still visible in is structure of the corn and by this very sticky. In the first step a group of men are slowing moving the rice in the usu (mortar).

This last for about 5 minutes. The men check the rice for its consistency and clean their mallets with fresh water. In the next step the the mochi is pounded with enthusiasm and force by a group of five or six ,until the mass of rice is smooth and shiny, with no discernible individual grains of rice.

They did this with several loads of rice, quite rapidly and never come across each other with their mallets. It looked like they were quite trained in this job.

Again the rice had to be examined.

Meanwhile the men were lining up for the –one person pounding–. I wonder if this was more effective than before. But certainly it served also the purpose to show the guests and the general public who was their most senior, their best etc….

The man next to the fresh water basket is turning the rice around so it is hit at a different place each time and he adds water, so the rice does not stick to the mallet. Another sequence..

The whole bounding of the mochi took about 15 minutes. Then the mochi was taken out the stump and brought to the women, who were waiting on the right side. Of course all clean and protected– it looks like a operation room…

Once the mochi is cooled down it will be served together with anko– japanese red beans.

Leave a Reply